|

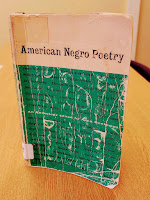

| With ye old library card intact; last date borrowed: 1984! |

There is a thin line between “bibliophile” and “hoarder.” When I happen across a bag, box, or table of library discards, the line blurs even further. A few years ago my school’s library was purging itself of older, out-of-date editions, and I could not resist rescuing a few titles from wherever books go to return to the earth. As often happens, however, they were saved from one dusty shelf (or more specifically from a plastic bag in the book room), only to settle onto another. Last week, with a few spare moments before classes ended and Presidents Week Recess began, I pulled a few volumes from the shelf of former discards for a closer look…

|

| Edited by Arna Bontemps. |

Claude McKay, for example, is referred to here by Bontemps as the “strongest voice” in “United States Negro poetry” since Dunbar (who is still widely anthologized in high school textbooks—with good reason). Prior to reading Bontemps’ anthology, I was unfamiliar with McKay and his writing. His poem “Outcast” begins with the powerful lines, “For the dim regions whence my fathers came/My spirit, bandaged by the body longs.” Those lines, in addition to the five poems included here, inspires me to seek out more. The possibility of discovering new authors for further exploration is just one of the great values of anthologies, even one that has been previously discarded.

A second draw of poetry anthologies like American Negro Poetry is finding that authors with whom one is familiar in one genre have also found success in another. Take novelist Richard Wright for example. While I, like most, have read Wright’s novel Native Son, this text introduced me to Wright the poet. Wright’s “Hokku Poems,” in particular, piqued my interest. On the page, the visual structure of the series of eight three line stanzas reveals the influence of Japanese haiku. While the opening line of stanza 1, “I am nobody,” suggest the political tone often associated with Wright, the content of stanzas that follow are much more playful and fun. Stanza 2, in particular, is a personal standout: “Make up your mind snail!/You are half inside your house/And halfway out!”

Bontemps continued to revise and update American Negro Poetry for decades with the most current edition (I could find online) coming out in 1995. As I think about the events that lead to this particular text being set aside, this understanding does provide me hope this older, worn edition was retired in favor of a more current one. The poetry in this anthology remains vital and relevant, while continuing to resonate.

No comments:

Post a Comment