A few summers ago, my interest in cryptozoology was rekindled. Initially nurtured in my childhood by a steady diet of my parents’ copies of World News and the National Enquirer, this interest has re-emerged thanks in part to a new interest in folklore as well as listening to a number of excellent crytpid and folklore related podcasts and reality television shows. Once a niche filed of ineterst, well-written and academic reading about such creatures as the Mothman, Bigfoot and others has also become much more readily available. Though there was magic in the halcyon days of Bat Boy, the writing has also become more polished, professional and consistently entertaining.

Due to the clean writing style and accessible nature of her

writing, Linda S. Godfrey has quickly found her way to my nightstand as one of

my go-to cryptid informer and literary palette cleansers. “One of America’s foremost experts on

mystery creatures”, Godfrey’s books take a journalistic approach to retelling

anecdotes and presenting histories of a variety of “monsters”, both familiar and unfamiliar.

American Monsters: A History of Monster

Lore, Legends, and Sightings in America spans an extensive timeline of

experiences, often relayed through first-hand accounts of a multitude of incidents with mysterious creatures. While re-reading sections this summer, I was also pleased to see the number of secondary sources from smaller publishes she references, in particular, those dealing with local or regional folklore.

|

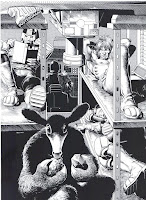

| "Wendigo" illustration, page 254. |

One of the book’s chief accomplishments, beyond being wildly entertaining, is taking advantage of opportunities to add additional layers of insight to those topics readers might incorrectly presume they have heard everything about. The expert here is clearly Godfrey and she’s come equipped with multiple approaches to each subject. An excellent example of this is the section entitled “Challenge of Chupacabres.” Having seen the X-Files episode as well as one or two short videos on YouTube, it might be easy to assume one has all the relevant information necessary to make a personal call on the existence of this “hell monkey”. While not offering a definitive answer on the existence of chupacabres, Godfrey does provide some examples of encounters and sightings with ancillary creatures that may be related to the Chupacabra phenomenon. Throughout the text, Godfrey also provides samples of photographic evidence and illustrations that range from the evidentiary to the ornamental. (As an aside, that evidence which is referenced throughout, but not included here, is readily available via a quick online search.)

American Monsters is a very entertaining and informative summer reading selection which continues to foster a personal interest in unusual creatures and the zeitgeist from which they sprang. In so many ways, each story is telling a small piece of the American story, which I continue to find fascinating. My guess is that if you take the chance to pick-up this unique tome, you will find the same.

*Originally posted 7/23/18, Revised 7/16/2020